In one of my recent blog posts, I addressed a common misconception I hear from concerned parents: that teaching your child to read early can lead to long-term harm for their social development and academic achievement.

And while we've covered why that misconception is false, it's unfortunately not the only misinformation shared on the internet that can be potentially harmful for our little ones.

Today, I'm going to cover one of the other biggest misconceptions floating around the parenting space: that engaging in academic material in preschool can have a negative impact on a child's future school performance.

People on the internet claim:

Children who receive academic instruction in preschool perform worse in the long-run than children who do not.

Where does this idea come from?

People often (mis)cite a study from the University of North Florida: Moving up the Grades: Relationship Between Preschool Model and Later School Success (Marcon, 2002). Let's explore what this study actually shows.

What did the study test?

In 2002, Rebecca A. Marcon conducted a follow-up to her 1992 study, in hopes of evaluating the impact of three different preschool models on later school success.

The original study included a cohort of 295 students randomly selected from one of three preschool learning models: child-initiated, academically directed, and "middle-of-the-road" (a combination of the other two models).

Marcon's 2002 study revisited the original students 4 and 5 years later to further evaluate how the differences in preschool models played out over time. Specifically, she checked in with 160 children across 61 schools 4 years later and 183 children across 70 schools 5 years later. Among the follow-up participants:

- 96% of students were African American

- 75% were eligible for subsidized school lunch

- 73% lived in single-parent households

Marcon evaluated later school success using the metrics of school retention, number of special education referrals, and grade point averages across all subjects.

What were the results?

Children who participated in a child-initiated preschool model outperformed their peers in the other models through the transition from early to later elementary school. Students who engaged in academically directed preschool experiences showed a decline in grade point average after their transition into fourth grade.

What do the results mean?

First, it's critical to acknowledge the lack of representation in the student sample to avoid taking results out of context and contorting them to mean something they don't.

Let's be clear: This is not a representative sample. With an overwhelming majority of the participants being African American, low-income, and from single family households, the results of this study shouldn't be generalized across a broader population.

Even within the demographic represented in this study, its small sample size (less than 300) and lack of relevant controls (e.g., the quality of instruction in each model, teacher experience, school funding, class size, as so on) make assuming replicability unreasonable.

And while these results are significant, they leave us with even more questions on which to base future research:

- What aspects of child-initiated learning led to future academic benefits?

- What parts of academically directed learning stunted academic performance in future years?

- Would these results be replicated for students of different socioeconomic statuses, races, and cultures?

- Would these results hold true when controlling for critical factors like teaching experience, class size, and so on?

Having more questions as a result of a study isn't a bad thing. The growth of our collective knowledge depends on us furthering our questioning every time we gather new information.

What is bad, though, is explaining the findings of this study in a way that misrepresents what they actually mean.

What do the results not mean?

The results of Marcon's study do not mean that teaching any type of academic content will do long-term harm. Because that's not the question being tested.

We must be crystal-clear on the fact that every child—in all three models—was taught something. The students in the child-initiated learning model were not placed in classrooms devoid of academic content. What differentiated this model from the others was how the children were taught and their ability to engage with the content in a different way.

In short, "child-initiated" doesn't mean these children weren't learning; it means they were learning in a different way than their peers who were a part of the other models.

Yes, the study showed students in the child-initiated model had better transitions from early- to later-elementary grades. But is that because the child-initiated model encouraged independence (as the lead author of the study speculated)? Or is it because child-initiated learning helped students develop a more positive outlook on school? Or is it because the academically directed model didn't allow for as many opportunities for social-emotional learning, which bolsters academic engagement in the long-run? It's hard to know from the design of the study.

We could hypothesize all day about why these children performed better and about what makes child-initiated learning more effective than the other models. What we cannot do, though, is equate academically directed learning with all learning. None of the evidence presented in this study supports the notion that teaching children to read before kindergarten does long-term harm; that is a logic leap that would require us to ignore the nuances of child-initiated vs. academically directed learning.

And yet, we've seen this study cited countless times by individuals criticizing those who want to expose their little ones to any amount of academic content before kindergarten (or in some cases, first grade.) It's irresponsible to twist Marcon's results to mean something they don't and that don't align with her purpose in conducting this study. If she wanted to answer the question as to whether teaching a child before kindergarten results in long-term harm, she would have studied that instead.

What's the bottom line?

The results of Marcon's study indicate the potential long-term academic benefits of structuring our preschools around child-initiated learning. Her results should not be misconstrued to argue that any type of pre-K academic learning will have a negative impact on future academic outcomes.

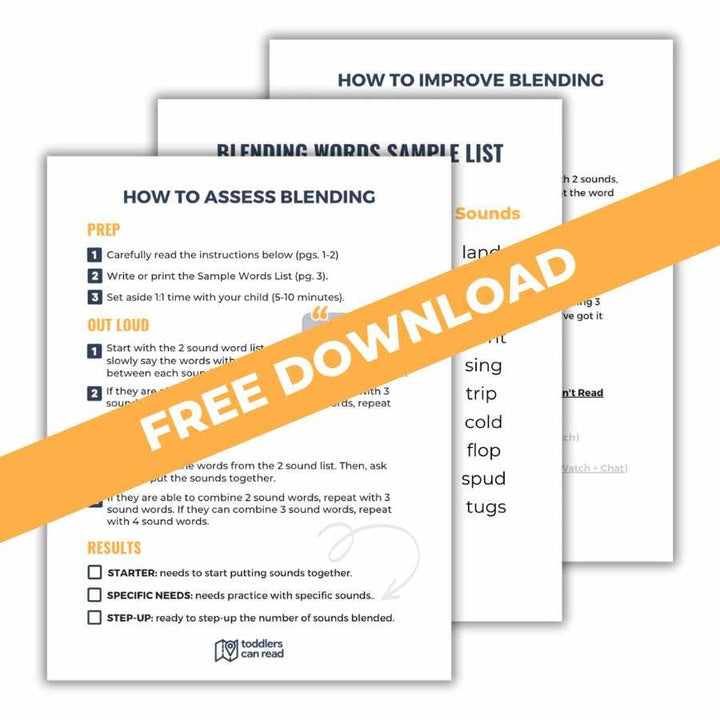

And to be clear: Toddlers Can Read has used these findings (and findings from other academic studies as well) to create our courses. We firmly believe that our little ones deserve play-based and child-initiated learning, and we want all of the resources we share to reflect that.

Designing our courses to be online and self-paced instead of through kill-and-drill worksheets was intentional. We knew that giving parents the tools to design lessons around how their child wants and needs to learn would be crucial in making the courses effective for all families.

As our courses continue to evolve into new versions with even more resources, we are committed to focusing on play-based, child-initiated learning that is informed by the science of how our brains learn to read. If you decide to teach your little one how to read, we want you to be able to do that in a developmentally appropriate, empirically-supported way.

None of this is meant to convince you that you have to teach your child to read before Kindergarten. Every child and family is different, and you know what is best for your little one better than anyone else does.

But, if you do decide to teach your child how to read before kindergarten, causing long-term academic harm should be the least of your worries.